Museo Universitario de Ciencias y Arte, MUCA Campus,

Mar 17, 2007 - Sep 30, 2007

Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico

Acts in Dissent. On the Age of Discrepancy: Art and Visual Culture in Mexico 1968-1997

by Gabriela A. Piñero

Although arising from the Mexican context specifically, those claims are also significant in a broader context. The dialogue and references that the works demand go far beyond the proposed territorial and spatial limits. México 1968-1997 only works as a simple initial approximation, a contextual reference. The work of los Grupos evokes the actions of different subjective elements that were also chosen in various parts of Latin America at the time in group work and the public sphere as a setting for action. On attempting to open a space through which to draw up and restate meanings collectively, Grupo Marco’s Poema Urbano (1980) offered a glimpse into a society marked by repression. During the same period, in other parts of Latin America that same situation of extreme violence determined the decision to intervene in a public space: the actions of the Colectivo de Acciones de Arte (CADA) in Chile between 1979 and 1985 were an attempt to denounce the conditions for existence that prevailed during the Pinochet dictatorship; Tiradentes - Tótem- monumento al preso politico (1970) by the Brazilian Cildo Meireles, also made use of public space to express the violence of the military regime that had been in power in Brazil since 1964; analogously, the collective action Siluetazo that took place during the Tercer Marcha por la Resistencia (Third March for Resistance, 1983) in Argentina sought to denounce the totalitarian regime in power since 1976, while also visualizing the forced disappearances that by that time already numbered some 30000.

These overlapping boundaries can also be traced in terms of time: the actions of the Grupos are an unavoidable reference for many current creators: the joint work of today’s and yesterday’s generations opens up new prospects for activities that seek to have a bearing on the present.(10) Following a meeting of art and politics held at the La Esmeralda National Art School (Escuela Nacional de Pintura, Escultura y Grabado La Esmeralda) in Mexico City, the members of H.I.J.O.S. México (Hijos por la Identidad y la Justicia, contra el Olvido y el Silencio ç Sons for Identity and Justice against Oblivion and Silence) came into contact with the Grupo SUMA. That initial contact led to a dialogue concerning the activities and experiences of each of the two associations, and for plans to carry out joint activities, which have yet to be defined. Grupo Suma thus calls for an approach to the past that, rather than a past to be evoked, views it as an ongoing practice, while also raising certain questions about the curatorial practice: how does one elude a representation that closes the chapter on something that is still alive? How does one point out what is beyond the exhibition rooms?

Chronos versus Kairos. Some authors who base their approach on Benjamin’s reflections characterize the different timelines which he views in terms of Chronos -as representing an objective, quantifiable period-- and Kairos - as the personification of an opportunity, of the right moment for action.(11) Questioned by the onlooker and memory, the different works exceed their proposed coordinates and invade a present that questions their functioning. The question that remains open is not only what past these practices seek to update, but also how that recovery should be approached: on the basis of what strategies these works seek to recover the past to which they refer. Pentágono (1977) by Proceso Pentágono proposes an idea of the past that, far from being conceived as an "objective piece of information" is being permanently reformulated from the present standpoint of whoever is bringing up the past. On reconstructing this piece for the exhibition, its authors did not hesitate to broaden its content by introducing references to subsequent events, such as the panel that refers to the demolition of Saddam Hussein’s statue in Baghdad in 2003. The work’s approach to the subject of torture emphasizes the multiplicity of memories to which these images refer.

Since the works exhibited form part of a period of cultural production in which many categories and frameworks of "belonging" began to be questioned, the curatorial approach raises doubts as to the way local historiography has been construed. The spilling over of categories seems to be the norm. Many have been taken up again just to show that they are inoperative. If what is national, along with its time frame, appears to be out of place, so are groupings such as "the geometrical". A closer look at this category and its "disarmament" reveals the interests vested in its "invention", as well as the projects and experimental work that were "crushed" in the determination to view a "similarity of style" as the only explanatory principle.

|

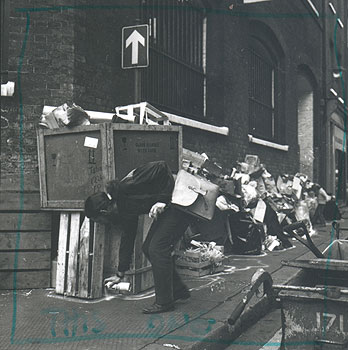

![Fábulas pánicas de Alexandro [sic] Jodorowsky 101 by Alejandro Jodorowsky](images/mx_discr_09_md.jpg)

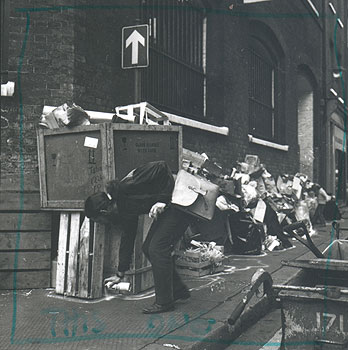

![Untitled [Eje Central Lázaro Cárdenas, México, D. F.] by Andrés Garay](images/mx_discr_11_md.jpg)

![Fábulas pánicas de Alexandro [sic] Jodorowsky 101 by Alejandro Jodorowsky](images/mx_discr_09_md.jpg)

![Untitled [Eje Central Lázaro Cárdenas, México, D. F.] by Andrés Garay](images/mx_discr_11_md.jpg)