Centro Cultural Recoleta ,

Dec 16, 2004 - Feb 27, 2005

Buenos Aires, Argentina

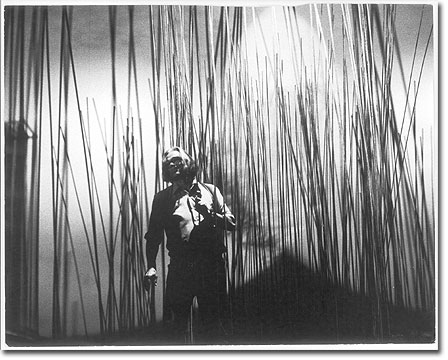

León Ferrari: Retrospective. Works 1954-2004

by Viviana Usubiaga

Pleasure and pain: the afflictions of the body

Action related to the body is another of Ferrari's preoccupations. His particular passion for woman has been evident since his first sculptures of stylized anthropomorphic forms in ceramic (Mujer, ca.1960; Mujer preocupada, 1961).He paid homage to Eve, treating her as a rebel that stood up to God, risked her life to obtain knowledge, released us from chastity, gave us pleasure and the human urge to investigate unknown paths as well as a taste for the fruits of good and of evil.

In recent months he prepared a series entitled Ideas para Infiernos, in which he took images of unhallowed saints and virgins and subjects them to fictitious torments. Inside a blender, in toy ovens, torn by paper clips or on a bazaar grill, the religious figures are subjected to martyrdoms similar to those promised mortal sinners in biblical Hell. Together with other pieces which critically manipulate Christian iconography, these humorous compositions have given rise to more than one scandal. In 1985 he exhibited a cage with two doves defecating on various reproductions of the Last Judgment at the San Pablo Museum of Modern Art. These works involving excrement criticize the visual artifices which have represented religious propaganda for centuries. Ferrari focuses on the areas where art served the relations of power, which seldom respond to spiritual interests. The result of careful study of the Holy Scriptures, his works question the punishment reserved for the bodies of our peers. The power of the gesture and the resulting rejection by the public, show that pity is selective and reserved for those wearing saintly garb.

The examination of different forms of intolerance becomes explicit in his 1995 illustrations for publication in the book Nunca Más (the report of the National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons during the military dictatorship). By means of a collage of images such as those of the Argentine Military College, the Nazi eagle and the of an Apocalyptic angel, Ferrari explicitly links the cruelties of the Old and New Testament to the crimes of a dictatorship sanctioned by a complacent Church and Nazi ideology.

This compulsion to assemble images, that are obvioiusly dissimilar, but that expose of the political interests to which they respond, continues with more current themes, such as scenes showing the hunger and corruption in Argentina, the Bush Empire (Electronicartes) and the war in Iraq, which he distributes periodically by email.

The language of the body and the body of language.

It is perhaps his series of Braille, mannequins and heliographs that produce the most intense synthesis of his main interests, writing and the body. His criticism of Western ideas on sexuality reach their most poetic heights in the braille series on nudes and in the collages that combine Catholic iconography, erotic Far Eastern illustrations and the nude bodies of Madonna or Cicciolina. Ferrari explains that the braille began with the idea of a blind Borges writing love poems on photographs by Man Ray, as though these were the girls he loved and to whom he dedicated these lovely poems, with the idea that one must caress the woman to read what the poet says. The subtle touch forms an unintelligible mark, their presence suggesting the pleasures of contact with the body. The graphics, now invisible, are an invitation to reflect on the pleasures of the senses, the eroticism of the image seen and the sensuality of the hidden words. Several of the selected poems reinforce this paradoxical play of presence and absence. In his 1997 work entitled En qu hondonada, Ferrari prints Borges poem "De ausencia" (Fervor de Buenos Aires, 1925) on a Man Ray nude (1929): ¿En qu hondonada esconder mi alma / para que no vea tu ausencia / que como un sol terrible sin ocaso / brilla definitiva y despiadada? Witness the absence of a body.

In 1979 he began a series of collages with the small Letraset figures used in architectural plans. He brings these prefabricated human forms together in the book entitled Hombres (1984) and Imagenes (1989), then continues them in large drawings and heliographic reproductions. Hundreds of men, women, rooms, beds, streets, motorways, and plants cover varieties of urban plans. The uniformity of these figures is aggravated by reproduction achieved by tracing and stamping, which operate as matrices within these microsocieties; in the overall drawing they seem to work as vowels in a disciplinary speech. The haphazard groupings making vision of singular bodies difficult, produces a text on alienation using preformatted figures. On the impossibility of showing the horror of the dictatorship in Argentina at that time, Ferrari argued that these works express the absurdity of present day society, a touch of daily madness necessary in order for everything to appear normal.

|