Espacio Fundación Telefónica,

Jun 21, 2006 - Aug 20, 2006

Buenos Aires, Argentina

Downey Effect

by María Fernanda Cartagena

Such wide-ranging recognition should not disguise the undefined place he holds in art history. It is easy to maintain that, despite his undeniable contribution, other criteria have been taken into account in establishing a genealogy of international or of regional video art (to name but one of the media favored by Downey). At the colloquium it was pointed out that he could not easily be classified within the established categories or tendencies of his time, so that his contribution and value may in fact lie in that very difference. The assimilation to internationalism, to cosmopolitism, or to Latin America’s vindication of art, comes into contention in artists such as Downey. The anomalous place that his work occupies and the difficulties one encounters in seeking to categorize it specifically, should lead to examining this tension as constitutive in the reception and value of his work. Both insider and outsider in various contexts, this splitting was a permanent and fertile conditioning of his work. Any approach to Downey must touch upon the contradictory and indefinable nature of his art.

The postcolonial criticism exercised by Downey, or more accurately, his links with the postwestern tradition, an approach that addresses and reviews the legacies of colonialism in Latin America, allows considering the artist’s "border thinking" ("pensamiento fronterizo"). A way of thinking that, in the epistemological proposal developed by theoretician Walter D. Mignolo, in his book Historias locales/Diseños Globales [Local histories/Global Designs], stems from the interference and "complementariness of modernity and of colonial status, of modern colonialism (since 1500 and its internal conflicts) and colonial modernisms, with their diverse rhythms and time spans, with conflicts between nations and religions during different periods, that are established in different world orders" (2003:138). Like many intellectual expatriates of that era, Downey came from a bourgeois family, left the third world at the outset of the dictatorship in his country, settled in the first world, and generated different poetic means of expressing such irreconcilable experiences.

The powerful intersection of his types of knowledge and languages can be perceived throughout his production, and his "double gaze" comes to the fore in a most exemplary way in his most ambitious and monumental project, the Video Trans America series (1973-1978). The videos from this series that were selected for the exhibition deal with his expeditions and encounters with the indigenous tribes of the Amazon Basin in South America, particularly the Guahibos and the Yanomami.

Downey pushed his medium and its genres to their limits. He transgressed the documentary by performing magical derivations with his camera in the direction of the most singular aspects of nature and their myriad reflections. He was able to register intimately both the material and the intangible aspects of these cultures, but, above all, he was capable of raising profound epistemological and ethical questions concerning the use of this medium from the perspective of colonial modernity.

Sketching a very general archeology, the Video Trans America series reflects an interest for the other as ancient as the mythological imagination through which the West lays the foundations of its identity, from the Eurocentric eye with which the white male subject fixes blacks, indigenous, or similar "primitive savages." Art contextualizes this process, as for example in the interdependence of colonialism, primitivism and modernism, which the cultural critic Hal Foster analyzed in his essay The "Primitive" Unconscious of Modern Art, or White Skin Black Masks, taking as a starting point Picasso’s paradigmatic painting Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. In another field, the birth of anthropology in the mid-nineteenth century used photography as a mechanism of power-knowledge over racial difference as part of the colonial expansionism.

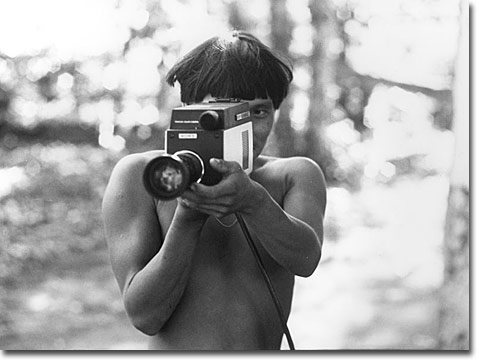

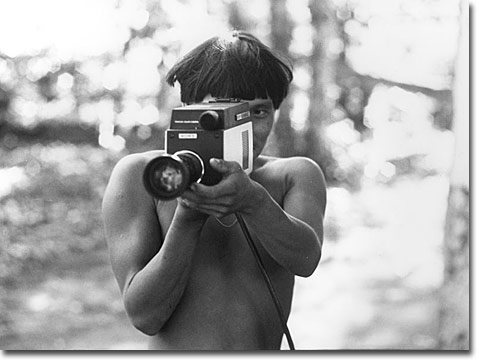

Downey participates in this project that is inherent to colonial modernity, as he points out at the beginning of his video Guahibos (1976), which forms part of the series and in which he films his shadow while justifying his expedition as part of his quest to find his true "self" in South America. Nonetheless, his radical contribution to art and anthropology lies in placing this encounter and exchange of glances with theother, as an opportunity for reflection in which the subjectification of cultures is resolved. Thus he strived to articulate a decolonializing gaze; he thought deeply about the inequities of this encounter as he delved into the complexity of exchanges and dialogues. This is what makes the dramatic climax of the series extraordinary, when the natives threaten him by pointing their hunting weapons at him while he "defends" himself with his video camera, and we become witnesses from the subjectivity of his point of view. The implications are equally profound when he hands over his camera to the natives for them to do the filming. This event triggers one of the most polemical contemporary post-colonial questionings advanced by Gayatri Spivak concerning intellectuals, power and representation: Can the Subaltern speak?

A Yanomami holding a video camera is an appropriate emblematic image for the show. The curator explains that, for a Yanomami, the camera means "noreshi towai" or literally "taking a person’s double." An action that, for the natives, unleashed the fear of their image being taken away while at the same time discovering the possibilities of obtaining feed-back from their reflection.

It is within this historical condition that, in this video series, language and translation is also ways of analyzing the power structures that dominate his work. Knowledge about these cultures is expressed in English and also in the voice of authority of a French anthropologist, but only a little in Spanish, while the native language remains distant and untranslatable.

In the startling video-installation About Cages (1987), the song of four caged birds and those broadcast by a video are superimposed with the "low voice" of the story of the Diary of Anne Frank and with the "authoritarian voice" of the de facto state through the confessions of a henchman of the Chilean dictatorship. Has it been too difficult or is it that no effort has been made to listen to these voices?

|